In this unit we will learn how to pronounce the 30 consonants and 4 vowels of the Tibetan alphabet. We will also learn the basics of the native Tibetan spelling system known as སྦྱོར་ཀློག་ jorlok. By the end of this unit, you will be able to pronounce words like ང་ (“I, me”), རི་ (“mountain”), and ཆུ་ (“water”).

Unit 1 Sections:

- 1. Introduction to the Tibetan alphabet

- 2. Overview of the 30 consonants

- 3. The eight rows of consonants

- 4. The four vowel letters

- 5. How to spell Tibetan words

- 6. Other notes on the alphabet

- 7. Terminology

1. Introduction to the Tibetan alphabet

The Tibetan languages have their own native writing system which has been in use for well over a thousand years. The Old Tibetan Annals relate that the Tibetan empire began to keep written records of historical and administrative matters in the year 650 CE. The Tibetan empire would ultimately collapse in the mid-ninth century, but the Tibetan writing system endured and has continued down to the present day.

The Tibetan writing system is popularly known as an alphabet in English-language sources, and in Tibetan it is simply called དབྱངས་གསལ་ yangsä, i.e. “the vowels and consonants.” The Tibetan alphabet consists of 30 consonant letters (གསལ་བྱེད་ säche) and 4 vowel letters (དབྱངས་ yang), making 34 letters in total. The order and structure of the Tibetan alphabet is modeled after the Sanskrit language, which has been the source and inspiration of so much of Tibetan culture through the centuries.

Tibetan writing does not use spaces between words; instead, it is broken up into syllables. It also has very few punctuation marks in common usage. Tibetan is written in various scripts, just like how English may be printed, written in cursive, written in shorthand, and so on. In this course we will learn the alphabet through the དབུ་ཅན་ uchän script, which is the main script used for the language. Uchän is read left-to-right, like English.

2. Overview of the 30 consonants

In this section I will give an overview of the 30 consonant letters and their general characteristics. Each consonant will be discussed individually and in detail later on.

In English, consonant letters have their own names such as cee, dee, jay, kay, el, and em. In Tibetan, however, the consonant letters do not have their own names, and so in the alphabet they are simply pronounced the same way that they’d be pronounced in an ordinary word. The Tibetan script does not make a distinction between upper or lower case letters.

The 30 consonant letters are traditionally arranged into 8 groups or rows (Sanskrit: varga, Tibetan: སྡེ་ de or སྡེ་པ་ depa) which are shown in the chart below. Below each letter I’ve written a representation of its pronunciation in English letters (“ka” etc.), which I will call the phonetic transcription. Below the chart is an audio recording of all 30 letters:

In this section we will discuss three features of the pronunciation:

- The default “a” that occurs after each consonant;

- The small letter h that shows aspiration;

- The underlines (e.g. a) that show low tone.

2.1. The default “a”

When read out loud, a consonant letter is usually followed by a short “uh” sound that we will call the default “a”. I have represented the default “a” with the letter “a” to show its pronunciation (e.g. “ka” for ཀ་), but it has no actual written letter of its own in Tibetan script. For this reason we could say that it is a vowel sound, but not a vowel letter.

A consonant letter is pronounced without a default “a” when it’s combined with one of the four vowel letters, or when it takes certain positions in a syllable. We will learn about these exceptions as we move through the course.

The small dot after each letter is a punctuation mark called a ཚེག་ tshek, and it is used to mark the end of a syllable. Its purpose is purely functional (similar to a space in English text), and it has no pronunciation.

2.2. Aspiration

Consonants in both English and Standard Tibetan are sometimes pronounced with a burst of air which is called aspiration. Consonants that are pronounced with a burst of air are called aspirated, and consonants that are pronounced without a burst of air are called unaspirated. Aspirated consonants are marked with a small h in the chart above.

An example of an aspirated consonant in English is the “p” in the word “pun”. If you hold your hand in front of your mouth and then say the word “pun”, you will notice a burst of air against your hand. For a more visual demonstration, you can hold a piece of paper or a lit candle in front of your mouth instead, and repeat the experiment.

By contrast, the letter “p” in the word “spun” is unaspirated – if you perform the aspiration test above with the word “spun”, you will notice that there is no big burst of air. Next, see if you can drop the “s” in “spun” while still keeping the “p” unaspirated. You should now be saying the word “pun”, but with an unaspirated “p”. It may sound similar to the English letter “b”, but it is actually just an unaspirated “p”, which is a sound that many English speakers aren’t used to hearing in isolation.

By going back and forth between the aspirated and unaspirated “pun”, you can start to train yourself to distinguish between aspirated and unaspirated consonants. You can also practice with other pairs, such as “kill” and “skill” (kh vs. k) or “top” and “stop” (th vs. t). This distinction may be hard to make at first if you’re not used to it, and you may find yourself tensing your throat to avoid making an aspirated sound. However, with practice you can learn how to make unaspirated sounds in a more relaxed way.

Standard Tibetan uses different letters for aspirated and unaspirated sounds, and aspiration helps to distinguish between different words. For example, consider the words ཀ་བ་ kawa (“pillar”) and ཁ་བ་ khawa (“snow”). These words are pronounced the same in every way except for the aspiration of their initial consonant; ཀ་བ་ uses an unaspirated “k” whereas ཁ་བ་ uses an aspirated “k.” (The pronunciation of the letter བ་ as “wa” will be discussed in Unit 3.)

2.3. Tone

Tone refers to the pitch of a sound in a language; high-pitched sounds are called “high tone” and low-pitched sounds are called “low tone”. Standard Tibetan is a tonal language, meaning that it uses different tones to distinguish between different words. Tonal languages may have complex distinctions in tone; for example, Mandarin has 4 main tones. Standard Tibetan, however, only distinguishes between 2 main tones: high tone and low tone.

In Tibetan, the tone of a syllable is determined by the consonant letter, but it is the following vowel sound that carries the high or low tone. The high tone is quick, sharp, and often falls slightly, whereas the low tone is longer, calm, and often slightly rising. In the phonetic transcription used throughout this course, high tones are left unmarked but low tone are marked by underlining the syllable’s vowel sound (for example, a).

Different letters of the Tibetan script carry different tones in Standard Tibetan. For example, the letters ཆ་ and ཇ་ have the same pronunciation except for their tone; ཆ་ is high tone and ཇ་ is low tone. However, both of these letters are also complete words; ཆ་ means “a pair” or “the same”, whereas ཇ་ means “tea”. So, if you mix up their tones, you will mix up the meaning of the sentence.

You may want to listen to the audio a few times while studying the chart to see if you can hear the difference between high-tone letters and low-tone ones. You can also practice saying the two letters yourself to get used to making the distinction in your speech, too. Don’t worry if it’s difficult at first; you’ll get better with practice.

Note that English does not use aspiration or tone to make meaningful differences between words. As a result, many English speakers struggle with learning to make these distinctions. You may find that many of the consonants sound the same; for example, ཀ་ཁ་ག་ might all sound like “ka”, or maybe some letters sound like “ka” and others like “ga”. By studying aspiration and tone, we can ensure that we properly learn the pronunciation of the consonant letters.

Quiz yourself

Standard Tibetan Unit 1 Section 2

We will now discuss the consonants in detail, one row at a time.

3. The eight rows of consonants

In this section I will describe sound of the consonants row-by-row. Each row of consonants is named after its first letter plus the word སྡེ་ de, so e.g. the first row is known as the ཀ་སྡེ་ ka-de, the second row as the ཅ་སྡེ་ cha-de, and so on. Many Tibetan words consist of only a single consonant; for example, ང་ means “I” or “me”, ཇ་ means “tea”, ཤ་ means “meat”, and ས་ means “earth”.

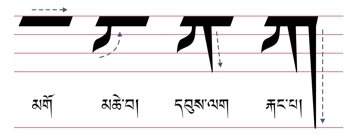

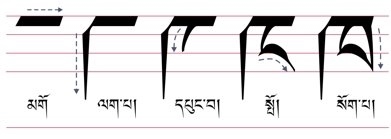

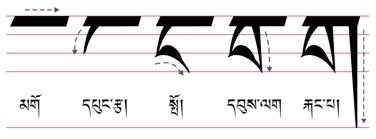

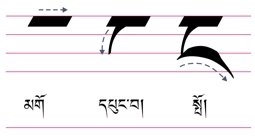

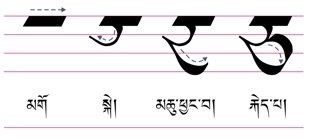

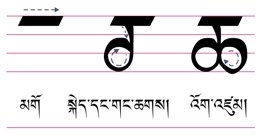

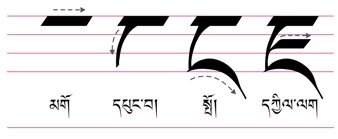

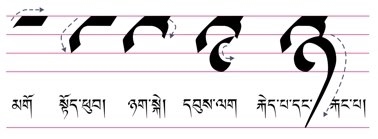

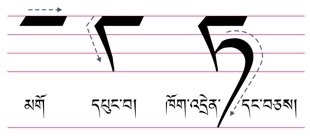

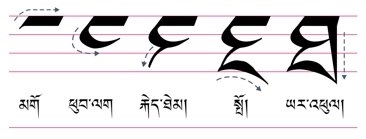

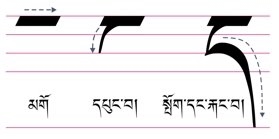

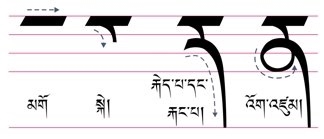

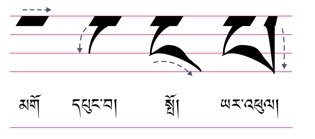

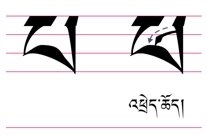

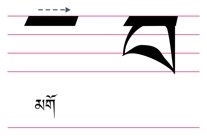

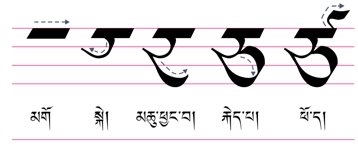

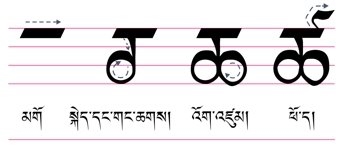

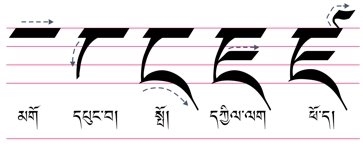

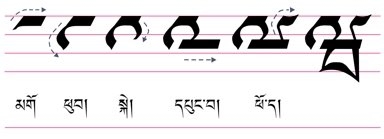

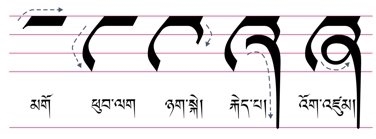

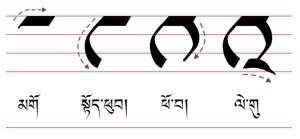

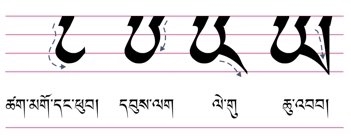

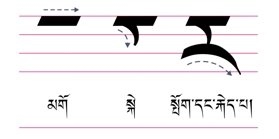

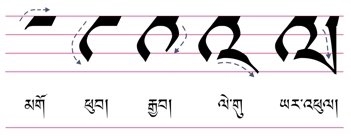

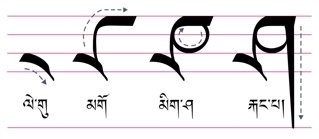

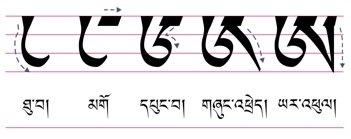

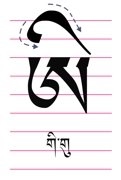

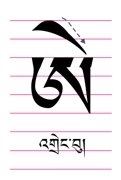

To learn how to write each letter, click on the ▶ symbol beside its description below. This will display an image of one possible stroke order for that letter. The images used were published by Christopher J. Fynn under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

Different resources teach different stroke orders, and in casual contexts it’s common for people to write in whatever way feels comfortable to them. Strict rules about stroke order and line thickness are more important in reed-pen calligraphy than in casual handwriting.

3.1. The first row

ཀ་

ཁ་

ག་

ང་

ཀ་ is an unaspirated, high-tone “ka” sound: ka

ཁ་ is an aspirated, high-tone “ka” sound: kha

ག་ is an aspirated, low-tone “ka” sound: kha

ང་ is a low-tone “nga” sound, like the “ng” in “singer”: nga

3.2. The second row

ཅ་

ཆ་

ཇ་

ཉ་

ཅ་ is an unaspirated, high-tone “cha” sound: cha

ཆ་ is an aspirated, high-tone “cha” sound: chha

ཇ་ is an aspirated, low-tone “cha” sound: chha

ཉ་ is a low-tone “nya” sound, like the “ny” in “canyon”: nya

3.3. The third row

ཏ་

ཐ་

ད་

ན་

ཏ་ is an unaspirated, high-tone “ta” sound: ta

ཐ་ is an aspirated, high-tone “ta” sound: tha

ད་ is an aspirated, low-tone “ta” sound: tha

ན་ is a low-tone “na” sound: na

3.4. The fourth row

པ་

ཕ་

བ་

མ་

པ་ is an unaspirated, high-tone “pa” sound: pa

ཕ་ is an aspirated, high-tone “pa” sound: pha

བ་ is an aspirated, low-tone “pa” sound: pha

མ་ is a low-tone “ma” sound: ma

3.5. The fifth row

ཙ་

ཚ་

ཛ་

ཝ་

ཙ་ is an unaspirated, high-tone “tsa” sound: tsa

ཚ་ is an aspirated, high-tone “tsa” sound: tsha

ཛ་ is an unaspirated, low-tone “dza” sound: dza

ཝ་ is a low-tone “wa” sound: wa

The first three letters of the fifth row appear very similar to those of the fourth row, but are distinguished by a small “flag” on the top-right corner. It is important not to confuse the two rows.

Note: ཛ་ has two different possible pronunciations. Some speakers pronounce it as an aspirated, low-tone “ts” sound (tsha) instead. I have used the pronunciation dza in this course because it seems more common to me.

3.6. The sixth row

ཞ་

ཟ་

འ་

ཡ་

ཞ་ is a low-tone “sha” sound: sha

ཟ་ is a low-tone “sa” sound: sa

འ་ is a low-tone “ɦa” sound: ɦa

ཡ་ is a low-tone “ya” sound: ya

The sound ɦ has an interesting pronunciation. It is most similar to the sound “h”, but it’s pronounced with the throat tensed so that the vocal cords vibrate. Beginners don’t need to worry getting it perfect right away because it’s a fairly uncommon sound. As with any aspect of Tibetan pronunciation, it’s best to practice the sound ɦ with a native speaker who can listen to you and teach you how to pronounce it more accurately.

3.7. The seventh row

ར་

ལ་

ཤ་

ས་

ར་ is a low-tone “ra” sound: ra

ལ་ is a low-tone “la” sound: la

ཤ་ is a high-tone “sha” sound: sha

ས་ is a high-tone “sa” sound: sa

3.8. The eighth row

ཧ་

ཨ་

ཧ་ is a high-tone “ha” sound: ha

ཨ་ is high-tone, and is not pronounced except for its default “a”: a

The letter ཨ་ is called a null consonant in Western scholarship because it contains no actual consonant sound, and is simply pronounced like whatever vowel sound it carries. We will see in the following section how to change the vowel sound of a syllable.

Quiz yourself

Standard Tibetan Unit 1 Section 3

4. The four vowel letters

Tibetan has four vowel letters. The vowel letters cannot stand independently on their own like the consonant letters can. Instead, the vowel letters must be attached above or below a consonant letter. Therefore, in order to talk about a specific vowel letter in isolation, the custom is to attach it to the null consonant ཨ་. The four vowel letters are:

ཨི་

ཨུ་

ཨེ་

ཨོ་

ཨི་ is pronounced like the “ee” in see

ཨུ་ is pronounced like the “oo” in too

ཨེ་ is pronounced like the “ey” in hey

ཨོ་ is pronounced like the “o” in so

The thirty consonant letters do not have their own names; each one is read the same way that it’s pronounced. The four vowel letters, however, do have their own names:

- ཨི་ is called གི་གུ་ khikhu

- ཨུ་ is called ཞབས་ཀྱུ་ shapkyu

- ཨེ་ is called འགྲེང་བུ་ drengbu

- ཨོ་ is called ན་རོ་ naro

4.1. Consonants + vowels

The vowel letters can be attached to any of the 30 Tibetan consonants to change the default “a” vowel sound. When a vowel letter is attached to a consonant letter, it takes on that consonant letter’s tone. For example:

- མེ་ me

- ཆུ་ chhu

- རི་ ri

- སོ་ so

These are all Tibetan words: མེ་ means “fire”, ཆུ་ means “water”, རི་ means “mountain”, and སོ་ means “tooth” or “teeth”.

Quiz yourself

Standard Tibetan Unit 1 Section 4

5. How to spell Tibetan words

Tibetan has its own native system of spelling known as jorlok (སྦྱོར་ཀློག་). Standalone consonants are spelled the same way they’re pronounced; for example, in order to spell ང་ we just say nga.

However, in order to spell a consonant that carries one of the four vowel letters (such as in the syllable ངོ་), we follow the procedure below:

- Pronounce the consonant letter by itself (ང་ nga)

- Say the name of the vowel letter that’s attached to it (ན་རོ་ naro)

- Pronounce the resulting syllable (ངོ་ ngo)

It’s kind of like we’re doing addition: ང་ nga + ན་རོ་ naro = ངོ་ ngo.

So, if someone is asked to spell the syllable ངོ་, they would say:

Give it a try: how would you spell the syllables མི་, དེ་, སུ་, ལོ་?

Think it through and write down how you’d spell each one, then compare with the answers below:

To practice your སྦྱོར་ཀློག་ jorlok listening skills, see this video.

We will learn more complex jorlok in Unit 2.

6. Other notes on the alphabet

This section contains various notes on the Tibetan alphabet.

6.1. Learning the alphabet

I recommend memorizing the 30 consonants and 4 vowels before continuing on to the next unit. A good way to memorize the alphabet is to practice writing the letters, or to use flashcards.

To practice writing the letters, you can use use this video by Sambhota Tibetan Schools Society, or this website by Chris Fynn. Alternatively, you can make a free account on archive.org in order to access the following e-book:

- ཡིག་གཟུགས་མིག་གི་བདུད་རྩི་ yiksuk mikki dütsi (p. 16-23)

- an alternate version (p.16-23) of the same book

- includes stroke order and direction for all letters

- uses traditional horizontal guide lines

- includes the Tibetan names of each stroke

The stroke order of Tibetan letters is not completely standardized, so different resources teach different stroke orders.

Now let’s talk about flashcards. Most Tibetan alphabet flashcards online are not ideal for our purposes, because 1) they use a transliteration system that’s not meant to represent speech sounds, or 2) they represent an accent other than the one that’s been presented in this course. The best flashcards for Standard Tibetan are the Anki deck 藏语字母-卫藏口音 (i.e. “Tibetan alphabet – Ütsang accent”). This deck focuses on audio only, and teaches the same accent as what’s taught in this course.

6.2. Languages and dialects

You may have heard people talk about the “different dialects” or “different accents” of “the Tibetan language”. In common speech, the terms “language” and “dialect” are political terms that are based on national and ethnic identity rather than on linguistic features. The term language refers to the language of a single nation or ethnic group, whereas the term dialect refers to the different varieties of a single language. The term accent refers to the pronunciation style of a particular language or dialect.

As a result, very similar languages are labelled as different languages (and not dialects) when the speakers of those languages identify with different nations or ethnic groups. An example of this is the Balkan languages, such as Serbian and Croatian, which are very similar linguistically but are usually referred to as different languages.

Conversely, very distinct languages may be referred to as dialects of a single language if the speakers all share a single national or ethnic identity. An example of this is the languages of China, such as Mandarin and Cantonese, which are often referred to as dialects of “Chinese” despite having many linguistic differences.

The terms “language” and “dialect” may help us understand people’s national or ethnic identity, but they don’t help us understand the linguistic relationships between different language varieties. If anything, these terms often obscure linguistic relationships because of the implication that two different dialects are more similar than two different languages, which may not be the case. The words lect or variety are more neutral terms which have no connection to the political or ethnic identity of the speakers.

Before discussing Tibetan lects in particular, we need to understand a bit of the history of the region. When the Tibetan Empire expanded in the seventh to ninth centuries, it brought the language of the Yarlung Valley (called Old Tibetan) as far west as Baltistan and as far east as Gansu. When the empire collapsed in the mid-ninth century, the Old Tibetan language continued to be spoken in those areas. However, by that time the language spanned thousands of kilometres of difficult terrain, and its speakers were no longer tied together by a centralized administration. As a result, the speech community began to fragment into many different local communities. As the speech communities fragmented, so too the language began to split into many different local varieties, each one similar to its neighbours but very different from the varieties in more distant regions.

This history can be compared to the collapse of the Roman Empire. The Roman Empire spread the Latin language throughout Europe and the Mediterranean, and when it collapsed, Latin began to fragment into various different languages. The languages that descend from Latin, the language of the Roman Empire, are called the Romance languages. These languages are spoken in many different regions — Spanish in Spain, French in France, Romanian in Romania, and so on — spanning many different nations and ethnic identities.

Likewise, the languages that descend from Old Tibetan, the language of the Tibetan Empire, are called the Tibetic languages. These languages are spoken in many different regions — Ladakhi in Ladakh, Ütsang Tibetan in Ütsang, Dzongkha in Bhutan, and so on — spanning many different nations and ethnic identities.

The term Tibetan or Tibetan language usually refers to any of the Tibetic lects of the three regions of Tibet: དབུས་གཙང་ Ütsang, ཁམས་ Kham, and ཨ་མདོ་ Amdo. These are tied together in modern times by a common Tibetan identity, hence why these different varieties are often called different dialects of Tibetan. This course focuses on the Standard Tibetan of the Tibetan Diaspora, which is very similar to the Lhasa dialect of Ütsang.

Source: 1

6.3. Kha lects and Ga lects

The Tibetan lects have many differences in pronunciation and grammar. By far the most common variation in Central Tibetan pronunciation is the distinction between what I will call Kha lects and Ga lects:

- Kha lects pronounce the letters ག་ཇ་ད་བ་ as kha, chha, tha, pha

- This is the pronunciation taught in this course

- Ga lects pronounce the letters ག་ཇ་ད་བ་ as ka, cha, ta, pa

- This may also sound like ga, ja, da, ba, hence the name “Ga lect”

Ga lects reflect the older pronunciation, are more common, and are more frequently represented in transliteration systems like Extended Wylie and transcription systems such as THL Simplified Phonetics, both of which use “ga” for ག་, “ja” for ཇ་, and so on. (For discussion of transliteration and transcription systems, see Unit 4 §4.) This sometimes makes students think that this is how Tibetan is always pronounced. However, Kha lects do exist, and are widely represented in the media of Central Tibet and the Tibetan Diaspora. This course teaches a Kha lect.

To hear the difference between the two, listen to the following videos:

- Kha lects:

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7kJ9fFMZfpc

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=inl9Z6Mh5xw

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=InuKqNkTnCo

- Ga lects:

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PUuU9Oj7DEI

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GiJQe3gabQw

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mmSmAhLnWFg

6.4. Summary

You can test yourself on Unit 1 as follows:

- Write out the full Tibetan alphabet, in order;

- Write down the phonetic transcription for each letter;

- Describe what aspiration is, and mark all the aspirated letters;

- Describe what tone is, and mark which letters are high tone or low tone.

- Recite the full alphabet.

However, don’t worry if you find that too difficult right now. You don’t need a perfect grasp of Unit 1 to continue, because I will remind you of any relevant aspects of pronunciation when they come up again in Unit 2.

Now that we know the basic Tibetan alphabet, we will learn in the next unit how to make more complex syllables.

7. Terminology

This section contains the important vocabulary (i.e. new Tibetan words) and jargon (i.e. technical terms in Tibetan grammar and linguistics) that we’ve learned in Unit 1.

7.1. Vocabulary

Audio:

ང་

I, me

ཇ་

tea

ཤ་

meat

ས་

earth

མེ་

fire

ཆུ་

water

རི་

mountain

སོ་

tooth

མི་

person

དེ་

that

སུ་

who

ལོ་

year

7.2. Jargon

Audio:

དབྱངས་གསལ་ yangsä

The vowels and consonants, i.e. the alphabet.

དབྱངས་ yang

A vowel letter.

གསལ་བྱེད་ säche

A consonant letter.

དབུ་ཅན་ Uchän

The main script used to write Tibetan.

སྡེ་(པ་) de(pa)

A group or row of consonant letters.

default “a”

The unwritten, default “a” sound of a Tibetan syllable. Represented by the letter “a” in the phonetic transcription.

ཚེག་ tshek

The small dot used to separate syllables.

aspiration

A small burst of air that’s pronounced after some consonants such as ཁ་ kha and ད་ tha. Represented by a small letter h in the phonetic transcription.

tone

The high or low pitch of a Standard Tibetan syllable. High tones are unmarked, and low tones are marked by underlining (a) bar on the syllable’s vowel sound in the phonetic transcription.

གི་གུ་ khikhu

The name of the vowel letter ཨི་ i.

ཞབས་ཀྱུ་ shapkyu

The name of the vowel letter ཨུ་ u.

འགྲེང་བུ་ drengbu

The name of the vowel letter ཨེ་ e.

ན་རོ་ naro

The name of the vowel letter ཨོ་ o.

སྦྱོར་ཀློག་ jorlok

The native Tibetan spelling system.

language

The language of a single nation or ethnic group.

dialect

The different varieties of a single language.

accent

The pronunciation style of a particular language or dialect.

lect / variety

A neutral term for a language or dialect, with no implication about the national or ethnic identity of a lect’s speakers.

Tibetic languages

The languages that descend from Old Tibetan, the language of the Tibetan Empire in the 7th to 9th centuries.

Tibetan language

Any of the Tibetic lects of the three regions of Tibet: དབུ་གཙང་ Ütsang, ཁམས་ Kham, or ཨ་མདོ་ Amdo.

Ga lect

A lect that pronounces ག་ཇ་ད་བ་ as ka, cha, ta, pa; or as ga, ja, da, ba.

Kha lect

A lect that pronounces ག་ཇ་ད་བ་ as kha, chha, tha, pha.